Ancrene Wisse or the "Anchoresses' Guide" (Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 402), written sometime roughly between 1225 and 1240, represents a revision of an earlier work, usually called the Ancrene Riwle or "Anchorites' Rule,"1 a book of religious instruction for three lay women of noble birth, sisters, who had themselves enclosed as anchoresses somewhere in the West Midlands, perhaps somewhere between Worcester and Wales. The author was apparently either an Augustinian canon or a Dominican friar, and by the time of the revision, Ancrene Wisse's readership had expanded to include a much wider community of anchoresses, over twenty in number according to the text,2 scattered mainly in the west of England.

This edition provides a reading text of the entire Corpus version.

Ancrene Wisse's Place in Literary History

It may at first seem startling that such a vivid and sophisticated vernacular prose as one finds in Ancrene Wisse (henceforth AW) and its related texts sprang to life in the Welsh borders and at a time (the early thirteenth century) when English was not at all a prized medium for serious religious instruction. AW, however, was written in a vernacular literary culture which in some senses stretched back to the late Anglo-Saxon period. The homilies of Ælfric and Wulfstan continued to be copied well into the twelfth century in Worcester, where they were also annotated and studied in the thirteenth. As Thorlac Turville-Petre writes, "This suggests a tradition of respect for works in English that must have itself acted as a stimulus to writings throughout the thirteenth century. Indeed, the quality and diversity of the English texts composed or copied in this region is striking."3 These texts include such important monuments of early Middle English as Layamon's Brut and The Owl and the Nightingale as well as MS Digby 86, which contains Dame Sirith, perhaps the earliest fabliau in English. The situation must have been different in the East Midlands, which gave birth to the much rougher Ormulum.

Thus, in West Midlands English, the AW author found a language already adapted to literary uses. R. W. Chambers, in his classic study, On the Continuity of English Prose from Alfred to More and his School, argued that the AW author carried on the work of late Old English writers such as Æthelwold and Ælfric, and that AW acted something like a linguistic Noah's arc, preserving English traditions in a time of Anglo-Norman and French deluge: "The Ancren Riwle therefore occupies a vital position in the history of English prose. Its popularity extends over the darkest period of our literature."4 As Bella Millett has pointed out, however, this view of AW and its related texts as vessels of "Englishness" ignores the strong continental influence on the AW's exegetical prose which was shaped in large part by twelfth-century Latin literature.5 Though it has some important connections to late Old English, then, AW's vernacular prose does not descend directly from it.

Why the Vernacular?

One question remains, however: Despite the fact that the AW author had a form of literary English at his disposal, it is not at first clear why he chose it as a vehicle for the rather advanced religious instruction of AW when, in the early thirteenth century, Latin or French would have been a more natural medium.6 One answer to this question lies in the nature of AW's audience, a group of quasi-lay women, some of high birth. Though they could apparently read French (see 1.340), the fact that almost all the Latin quotations are translated into English suggests that their literacy in Latin was limited and thus that they were not nuns. AW was composed in English, then, because it was written for lay people, though of a very special type (see the section on "Audience" below), because it was written for women (whose educational opportunities were much more restricted than those of men), and because it was composed in a region which valued English literary culture.

The Anchoritic Life

Medieval anchorites, as strange as it may seem to us, sought to withdraw so radically from the world that they had themselves sealed into cells for life. In fact, the word anchorite comes ultimately from the Greek verb anacwre-ein, which means "to withdraw." Anchorites (both men and women) withdrew from the world not only to avoid physical temptation, but to engage in the kind of spiritual warfare practiced by desert saints like St. Anthony (the founder of Western monasticism), who around 285 A.D. wandered into the Egyptian desert searching for God through complete solitude and who attempted to tame the wickedness of the body with physical suffering and discipline.

Desert Spirituality

In the fourth and fifth centuries, a number of holy men and women like St. Anthony retired to the Egyptian desert to seek a severe life of solitude. In many senses they were something like spiritual athletes. In fact, the word ascesis (from which asceticism derives) referred originally to the regimen of exercise practiced by athletes. AW refers admiringly to some of the superstars of the desert: Anthony, Paul the Hermit, Macarius, Arsenius, Sarah, Synceltica, Hilarion, retelling their feats of perseverance and discipline from a text known as the Vitas Patrum (The Lives of the [Desert] Fathers).7 Peter Brown manages to recapture some of the excitement of desert spirituality, and his remarks are worth quoting at some length:

Another aspect of desert spirituality which profoundly influenced AW is its sense that the spiritual life requires an almost physical battle against the devil. The following anecdote is told about Helle, a desert saint:

Becoming an Anchorite

To become an anchorite in England (from the twelfth century on) involved making an application of sorts to a bishop. As Ann K. Warren makes clear in her study Anchorites and their Patrons in Medieval England, bishops had the primary responsibility for investigating the claims of any would-be anchorites:

Rites of Enclosure

As Warren notes, one of the duties of the bishop was to officiate personally or through a deputy at the enclosure of the anchoress, and several enclosure ceremonies survive in pontificals (i.e., handbooks for bishops, containing the texts of rites and sacraments which they must perform).15 Though there are a number of variations, the enclosure ceremony usually includes the following elements: an anchorite receives last rites, has the Office of the Dead said over her, enters her cell, and is bricked in, accompanied at each stage by various prayers.

Attractions of the Anchoritic Life

For late twentieth-century readers, the inevitably macabre drama of enclosure fails to convey why more and more women in the course of the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries were drawn to a life of perpetual enclosure. Warren charts the number of anchorites in England from the twelfth through sixteenth centuries and shows that women far outnumbered men, particularly in the thirteenth century:

Numbers of Anchorites: 1100-153916

What drew so many women to the anchorhold? One answer may be that, in a strange sense, many anchorites withdrew from the world only to find themselves squarely in the center of village life. We can perhaps glimpse this obliquely in a list of prohibited activities for anchoresses in Part Eight of the AW. There, the AW author advises anchoresses not to keep valuables in their anchorholds (8.89-92), run a school (8.162-65), or send, receive or write letters (8.166). Further, in Part Two, the author warns his readers that the anchorhold should never become a source of news or gossip (2.486-88). These prohibitions offer a tantalizing glimpse into some of the social functions of the typical anchoress in her village setting. At least some anchorholds, it seems, became the center of town life, acting as sort of bank, post office, school house, shop, and newspaper - services which today are provided mainly by public and quasi-public institutions. The AW author, of course, advises against these activities mainly because they draw the heart of the anchoress outside her anchorhold, but that they must be prohibited points to the fact that many anchorites became something like spiritual celebrities - they became the focus for the communal religious life of the village. Warren suggests that the

Some anchoresses achieved enough celebrity that they were sought out as spiritual advisors. In the twelfth century, the anchoress Christina of Markyate became the confidant and advisor to Geoffrey, the powerful abbot of St. Albans, and in the fifteenth century, Margery Kempe consulted Julian in her anchorhold in Norwich.17 AW assumes that the faithful will come to the anchoresses for advice - though such visits from men may not be entirely desirable - and suggests, "If any good man has come from afar, hear his speech and answer with a few words to his questionings" (2.270-71). A bit later, however, the AW author takes a somewhat sterner position: "[Do] not preach to any man . . . nor [should] a man ask you [for] counsel or tell [it] to you. Advise women only" (2.280-81).

Attraction of Anchoritic Community

Not only did an anchoress become part of a village community, but AW strongly suggests that she also entered into an anchoritic community as well. At first glance, this seems a rather absurd idea - that a woman would enter a cell and be bricked in by herself in order to find a communal religious life. But AW does spend a good deal of time discussing the joys of and impediments to communality. Part Eight reveals some details about how this community functioned: anchoresses communicated with one another through a network of "maidens" or servants who carried verbal messages to other anchoresses (see the section on "Audience" below).

Daily Life of Anchoresses

What was daily life like for the anchoresses for whom AW was written? In their edition of Part One, Ackerman and Dahood offer a glimpse of the anchoresses' daily activities in the following itinerary, reconstructed from Part One's advice about liturgy and prayer:18

For further information on the liturgical forms presented in this table see the Explanatory Notes for Part One.

Architecture of Anchorholds

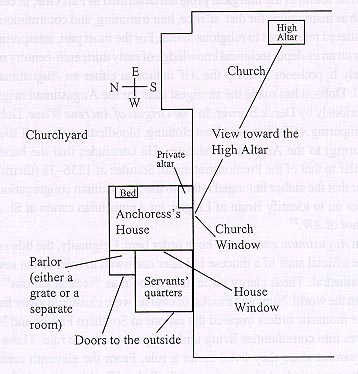

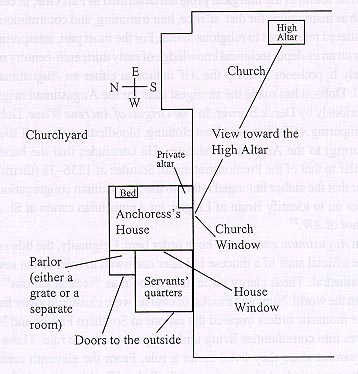

Very few anchorholds survive from the Middle Ages - after the death of the anchorite, they seem to have been demolished, converted to other uses, such as vestries, sacristries, or chapels, or obscured by further construction. In Chester-le-Street, near Durham, a surviving late medieval anchorhold consists of two large rooms, one on top of the other, built into the northwest side of the church. The upper room has a squint (i.e., a slit or small window) offering the anchorite a view of the side altar which was reserved for public use. Even in the case of Chester-le-Street, however, the surviving cell has been altered considerably (having been converted into an almshouse after the Middle Ages by the addition of two rooms), and part of what was the anchorite's lower room now houses the boiler for the church. It seems that anchorholds could range in size from a single small room to a set of apartments with an inner garden, some with servants' quarters and some without. Locating and identifying anchorholds, then, is a difficult business which involves a combination of archaeological investigation, documentary history, and guesswork. Surveying descriptions of anchorholds, Clay concludes that many were on the north side of the churches to which they were attached, perhaps to expose them to the cold northern winds.19 Warren notes that though not typical, it was not unheard of for two anchorites to live in adjoining cells.20 Only Parts Two and Eight offer any substantial hints about the internal arrangements of the anchorhold. One suspects that the very specific details of Part Two may have applied more to the living conditions of the original three sisters than to those of the twenty-plus anchoresses, whose houses must have taken a variety of forms. And in fact, the prescriptions of Part Eight seem more vague.

The anchorhold described in Part Two could have had two or three rooms:

There is some question about what the world parlur may have meant. The following two definitions from the Middle English Dictionary seem most relevant: "(a) A chamber in a religious house used for consultation or conversation, esp. for conversation with persons outside the monastic community; (b) a grate or window through which the enclosed religious can make confession or communicate with persons outside the cloister." The evidence in AW tends to suggest that the parlur was a separate room: Part Two refers to "your parlor's window" (ower parlurs thurl, 2.203) and says that of all the windows, "the parlor's window be the least (i.e., smallest) and narrowest" (2.16-17). It seems unlikely that parlur could refer to a simple grate or window, since "the grate's window" makes for a difficult sense. Whether a separate room or merely a window, however, the parlor must have been visible from the servants' quarters since AW advises an anchoress to check with her maiden to see who is at the parlor window before deciding whether or not to open it (see 2.203-04).

The servants' quarters must have been reasonably large since anchoresses were encouraged to have guests entertained there ("If anyone has a cherished guest, [let her] have her maidens, as if in her place, entertain her fairly. And she will have permission to unblock her window once or twice and make signs toward her (i.e., the guest) of a fair welcoming," 2.263-65). Some anchorholds must have had a door between the servants' quarters and the cell proper since AW warns against dining with guests at the same table: "Some anchoress (i.e., sometime an anchoress) will sit to dinner (lit., make her board) outside with her guest (ute-with). That is too much friendship" (8.30-31). Further, anchoresses are advised to invite the visiting maidens of other anchoresses to spend the night, presumably in the servants' quarters (see 8.62-64).

The following diagram attempts to account for as many of the preceding details as possible, though of course the positions of the rooms may have varied considerably.

The Anchorhold as described in AW: A Conjectural Reconstruction

Authorship

Since Morton's 1853 edition of AW, scholars have attempted to attribute AW to the pen of a number of writers: Simon of Ghent, Richard Poor (Bishop of Salisbury, d. 1237), Gilbert of Sempringham (1089-1189), Robert Bacon, the hermit Godwine, and Brian of Lingen.21 None of these attributions has proved ultimately very convincing, and perhaps the best we can hope for is to know what sort of person, but not exactly who, the author was.

So far, the detective work has focused on clues which might reveal the religious order to which the AW author belonged. The author refers to his order obliquely in his instructions for taking communion in Part Eight: "Therefore you should not receive the Eucharist-except as our brothers do-fifteen times within a year" (8.9-10, italics mine).22 The most promising evidence for such an approach is clearly to be found in the liturgical program described in Part One, in certain practices of the outer rule (such as instructions for diet, silence, hair trimming, and communion) described in Part Eight, and in scattered references to religious habits. For the most part, interpreting these clues successfully depends on an in-depth technical knowledge of early thirteenth-century religious rules. The two most likely hypotheses identify the AW author as either an Augustinian canon or a Dominican friar. E. J. Dobson has made the strongest case for the Augustinian origins of AW, an idea first proposed seriously by Derek Brewer. In The Origins of Ancrene Wisse, Dobson carefully builds his case by comparing AW's dictums about clothing, bloodletting, vows of silence, diet, and hair trimming (tonsuring) to the Augustinian statutes. He concludes that the handling of these practices is very similar to that of the Premonstratensian Statutes of 1236-38 (themselves derived from earlier rules) but that the author belonged rather to the Augustinian congregation of St. Victor (p. 113). Dobson goes on to identify Brian of Lingen, an Augustinian canon at St. James priory, Wigmore, as the author of AW.23

A word on the term Augustinian canon may be in order here. Originally, the title canon referred to any member of the official staff of a diocese but later narrowed to refer to the several ranks of clergy serving in a cathedral. These clergy came to be known as "secular canons" because they pursued their calling in the world. Nuns and monks, of course, were cloistered away from the world, but the prestige of the monastic orders inspired the canons in Southern France and Northern Italy to organize themselves into communities living under a quasi-monastic rule. These canons were known as "regular" canons since they lived under a rule. From the eleventh century on, most communities of regular canons adopted some form of the Rule of St. Augustine. In fact, at least four different texts circulated under this title, only two of which were arguably written by Augustine himself: the "Precept," a set of instructions written for men at Augustine's home monastery at Hippo, as well as a rule for women based on Augustine's Letter 211, but prefaced with other material. Until the end of the thirteenth century, individual houses of Augustinian canons such as St. Victor in Paris did not operate under strong centralized control and were relatively free to develop their own variations on the rule.24 In general, the Rule of St. Augustine, in its various forms, looks to the early church for its view of an apostolic Christianity ministering to the sick and poor. In their collection of monastic, canonical, and mendicant rules, Douglas J. McMillan and Kathryn Smith Fladenmuller write that "Augustine essentially called for having all possessions in common, common times of communal prayer, no individual distinctive clothing, and strict obedience to the leader of the community" and that the "canonical life was thought of as one of compromise, halfway between that of the secular clergy and that of Benedictine monks."25

As Bella Millett and others have pointed out, some of the practices which Dobson assigned to the Augustinian canons have more exact parallels in the legislation of the Dominicans.26 Dobson fended off this suggestion (advanced by McNabb and Kirchberger) by pointing out that Dominican customs evolved from the Augustinian rule and that any resemblances between the practices of AW and those of the Dominicans must be assigned to earlier, and in some cases, lost Augustinian statutes.27

Recently, Millett has made a strong case for reconsidering Dobson's reasoning. In reviewing the research since the seventies, Millett concludes that practices revolving around communion, tonsure, and the reciting of the Office of the Dead are in most cases closer to Dominican practice, though the first surviving record of some of these practices comes from a later document, the first Dominican Ordinarium of 1256. On other points, AW seems to stand in very close relationship to the Premonstratensian statutes of 1236-38. The Premonstratensian canons - named for the place of their foundation, Prémontré, near Laon - formed an independent congregation operating under an Augustinian Rule. Through his friendship with St. Bernard of Clairvaux, their founder St. Norbert brought the order under Cistercian influence. Millett suggests that practices in AW which most resemble those of the Premonstratensians "are of Dominican origin, but date from a transitional period, the two decades following 1216, when Premonstratensian and Dominican customs were running closely alongside each other and local Dominican practice was still far from uniform. Their links with Premonstratensian legislation could then be explained by the initial and continuing influence on Dominican practice of the Premonstratensian statutes."28

Implications

At first, it may seem that attributing AW to an Augustinian canon or a Dominican friar is a technical matter which makes little real difference to understanding the evolution of the text. However, placing AW in the sphere of the Augustinians or Dominicans does have a number of interpretative implications. By the early thirteenth century, the Premonstratensians had become almost indistinguishable from other monastic communities, and thus an Augustinian AW would best be understood as a representative of current monastic concerns (under the heavy influence of St. Bernard's theology). A Dominican origin for AW, on the other hand, implies a program much more oriented towards lay spirituality, and would explain the heavy emphasis on penance and confession (Parts Four, Five, and Six), directed apparently at a general audience (see the section on "Audience" below). The Dominicans, as Millett points out, "were actively involved in the implementation of the programme of pastoral reform laid down by the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215; one of their main functions was to assist the bishops with their increased pastoral workload by preaching, the hearing of confessions, and the provision of spiritual advice."29

The order was founded around 1220 by St. Dominic, one of the great preachers of the age, to help combat the rising tide of heresies popular in southern Europe. To reach lay audiences, new emphasis was placed on such devices as exempla and comparisons (similitudines) drawn from the everyday world of the laity as well as references to phenomena in the natural world drawing on beast lore, lapidaries and herbals. In the course of the thirteenth century a whole new array of reference works and preacher's tools came into being, perhaps the most notable of which were alphabetized or indexed collections of sermon stories, many of them compiled by Dominicans.30

In many ways, this new interest in orthodoxy and pastoral care gave lay women fresh oppor-tunities for organized religious life. Jacques de Vitry, one of the great preachers, played a hand as a confidante of Mary of Oignes, in the founding of the Beguine movement in the Netherlands,31 and it is perhaps no coincidence that in England the AW's community of twenty or so anchoresses were forming in the west country at about the same time, and that their spiritual director, like Jacques de Vitry, was also steeped in the new methods of preaching.

In the course of the thirteenth century, the Dominicans spent more and more time acting as spiritual advisors to women. In fact, Emicho of Colmar became the first Dominican to gather a group of recluses into a regular community in the early 1220s.32 Some within the order, particularly Jordan of Saxony, however, began to have reservations about the wisdom of supervising women, since it was occupying more and more of the order's time and resources, and in 1228 the chapter attempted to stop any new relationships of this sort: "In virtue of the Holy Spirit and under pain of excommunication we strictly forbid any of our friars from striving or procuring, henceforth, that the care or supervision of nuns or any other women be committed to our brethren . . . we also forbid anyone henceforth to tonsure, clothe in a habit, or receive the profession of any woman."33 This ruling did not put a halt to Dominican involvement in the Beguine movement, however. Interestingly, the Premonstratensian canons had been similarly released from supervising women in 1198.34

Collaborative Authorship

The quest to identify the author of AW may have been hampered by a narrow conception of authorship which assumes a single, authoritative creator for a text. It is possible to imagine clusters of anchoresses copying and reading AW intensively, interpreting and responding to the text, sometimes prompting the author (their spiritual advisor or advisors) to clarify, expand, or revise the text. One could perhaps go further, to suggest that some of the revisions and additions to the text may have been made by the anchoresses themselves (since they acted as scribes), perhaps originally as marginal glosses which were incorporated into the main text at the next copying.35

First and foremost, it is important to realize that what Tolkien called the "AB language," the language in which the various versions of AW were composed (see the section on "Language" below), is a communal language, with its own distinctive vocabulary, syntax, and spelling system. The unusual degree of standardization implies a strong sense either of hierarchical control of texts or, alternatively, of community investment in a common language. Not only the original author but also the scribes and presumably readers were well versed in the dialect and its conventions, since it served as the major socio-linguistic glue for the community. In fact, the idea of a communal language may muddy the waters of authorship here - "style" is not so much a matter of individual personality as communal convention, and it may be difficult to distinguish between contributions by different members of the community.

Audience

The original audience of AW apparently consisted of three sisters of noble birth. The Nero version preserves a passage (omitted in Corpus and much abbreviated in Cleopatra and Titus36) which addresses the three sisters directly on the topic of external temptations and hardships:

Expanded Audience

By the time of the Corpus revision, the audience had expanded to a group of twenty or more anchoresses spread in the west of England, as the following added passage shows:

Community

The kind of community implied in the passage cited above is difficult to account for precisely. The anchorholds must have been far enough apart so that they would cover a territory reaching to the "end of England." On the other hand, they must have been close enough to each other for the servants or maidens of the anchoresses to travel easily between anchorholds. The following passage from Part Four implies a rather intimate connection between anchoresses in that it allows for complex communication between anchorholds via messengers:

Part Five, the section on confession, seems in particular to be directed at a mixed audience including nuns, anchoresses, virgins, married women, and even men: the author clearly had an interest in instructing a variety of people, both religious and lay, about the new sacrament of confession, perhaps further evidence that he was a Dominican. In explaining the circumstances or "trappings" of sin, he provides a sort of fill-in-the-blank confession: "I am an anchoress, a nun, a wedded wife, a virgin, a woman that was trusted, a woman who has been burnt before by such things . . . . Let each person, according to what he is, describe his circumstances, a man as it applies to him, a woman what touches her" (5.216-18, 247-48).

Near the end of the section he explains that the sixteen attributes of confession have not been written specifically for the anchoresses:

Part Six, I would argue, also has a dual audience, but of a different kind. Here, the author seems to be addressing both advanced anchoresses (perhaps the original three) as well as newcomers to the anchoritic life: "Everything that I have said about the mortification of the flesh is not for you, my dear sisters - who sometimes suffer more than I would want - but is for someone who may readily enough read this, but who handles herself too softly" (6.376-78). He goes on to describe this indulgent anchoress (or perhaps lay woman) as a young seedling which needs to be protected from the devil by a circle of thorns (i.e., pain), another image of enclosure. This same phenomenon may be at work in a passage discussed above which begins by addressing the entire group of twenty anchoresses, who are spreading to the end of England, but which seems to end with praise for the original anchoresses, who "are like the mother-house from which they are born" (4.927-28).

Date

Though none of the versions of AW can be dated with absolute certainty, the two references to the Franciscans and Dominicans in the Corpus manuscript (both lacking in the other versions) narrow the date of the Corpus revision to the period after the arrival of the Dominicans and the Franciscans in England (1221 and 1224 respectively):

Localization

By a process of elimination, the language of AW can be localized to the West Midlands. We know that it did not come from the South since it lacks typical features of late West Saxon; it cannot come from the more northerly dialects because of its verb endings; and it cannot come from the Eastern Midlands because of the distinctive way it spells OE y and eo (see d'Ardenne, Seinte Iuliene, pp. 179-80). In addition, AW contains one, possibly two words of Welsh origin: cader "cradle" and perhaps baban "baby" (see glossary). This linguistic evidence, coupled with the inscription on the first folio of the Corpus version indicating that the manuscript was given to St. James priory in Wigmore, led Dobson to locate the author and thus the text in the vicinity of Wigmore, approximately forty kilometers to the northwest of Worcester and less than twenty kilometers east of Wales (Dobson, Origins, chapter 3). More recently Margaret Laing and Angus McIntosh have suggested that the original AB dialect should perhaps be placed further north. It should be noted, however, that the scant number of early texts which can be firmly located makes dialect mapping for this period very difficult. Nevertheless, the forthcoming Linguistic Atlas of Early Middle English may be able to add more precision to the general picture we already have.

Structure

The overall structure of AW, as the author outlines it in Pref.130-51, is relatively straightforward: it consists of eight parts, the first and last devoted exclusively to the outer rule, the middle sections to the inner rule. An extensive outline of each individual part appears in the Explanatory Notes, so I will characterize them only briefly here.

The Preface establishes the difference between the outer rule, which governs the external behavior of the anchoresses in matters of prayer, food, clothing, etc., and the inner rule of the heart, which is the far more important goal of the anchoritic life. In fact, the outer rule should be a mere servant to the lady of the inner rule.

Part One gives basic recommendations for daily prayer.

Part Two, though difficult to describe briefly, shows the anchoress how to regulate her five senses so that the outside world does not intrude into her anchorhold through the dangerous portals of eyes, ears, nose, mouth, or hands. To compensate for this loss, the anchoress will have delight in a set of inner senses: spiritual sight, taste, touch, etc.

Part Three stresses the importance of regulating the inner life (in distinction to Part Two which focuses on the external senses) by comparing anchoresses to birds with various allegorical properties.

Part Four catalogues various branches of external and internal temptations, organized around the concept of the seven deadly sins. This massive section also includes remedies against and comforts for each temptation.

Part Five turns to the subject of confession, listing the sixteen attributes of good confession, while Part Six explores the concept of penance and becomes in effect a general meditation on the value of suffering rather than a manual on sacramental penance.

Part Seven, the climactic chapter of AW, maintains that divine love, not pain and penance, is the highest goal of the anchoritic life, likening the love of Christ to that of a knight whose recalcitrant mistress refuses his advances. Part Seven also likens God's love to Greek fire, a kind of medieval napalm.

Part Eight returns to the concerns of the outer rule, giving various recommendations on such varied topics as clothing, diet, observing silence, manual labor, keeping pets, entertaining guests, and dealing with servants.

The author's concern for organization (seen in the summary of chapters at the end of the preface) also reveals itself in the physical layout of the book. As Dahood has observed, both Corpus and Cleopatra employ a system of capital letters of varying sizes to indicate different levels of subdivision within the text, a system which Dahood believes may have been put in place in the exemplar of Cleopatra. Though in Corpus the system begins to lose its consistency after a few folios, it is clear that, in Dahood's words, "Whoever first imposed the system of graduated initials was concerned that readers grasp the relationships between divisions and not just focus on discrete passages" ("Coloured Initials," p. 97).

Language

J. R. R. Tolkien first coined the term "AB language" in 1929 to describe the remarkable orthographic and linguistic consistency he noticed between the Corpus version of Ancrene Wisse (manuscript "A" in Hall's Early Middle English) and Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 34, containing a complete selection of what is now called the Katherine Group (Hall's manuscript "B"). These remarkable similarities (despite the fact that the two manuscripts were written by different scribes) suggest that the original texts were written in roughly the same place and time (Tolkien, p. 111). The term "AB language" is now rather baffling - since few now refer to Corpus as "A" or Bodley 34 as "B," but it has stuck, for better or worse. What is remarkable about the AB language is not so much that it represents a distinctive regional dialect, but the fact that it is really a kind of standard written language, descended in part from late Old English, and such a standard implies a common literate community.

What are the characteristics of AB language? S. R. T. O. d'Ardenne undertook a thorough description of it in her edition of the life of St. Juliana (one of the Katherine Group texts) and reports the following features:

Spelling

Since the AB language is conservative and resists some Norman conventions which modern English has inherited, the spelling system of AW often obscures a word which modern readers might otherwise recognize. The following chart lists a few of the most common or confusing spellings in AW along with their modern equivalents.

Reduced Spellings

In a few cases early ME contractions and consonant reductions (as reflected in the spelling system) can make words difficult to recognize. Two of the most difficult involve the th sound. In the first, the th- at the start of any word is reduced to a simple t if the sound immediately before it (the last sound in the preceding word) is a t or d.

Nouns

The main difficulty in interpreting nouns comes in deciding their number (singular or plural) and whether or not they are possessive. As the following chart shows, the AB language had a number of different methods for signaling the plural (see the "summary" column) derived from a much more complicated gender-based system in OE. Though this system survives to a certain degree in the AB language, a majority of nouns form plurals with either -es or -en. The possessive singular is usually easy enough to identify in that it takes the -es familiar to speakers of modern English. More difficult is the possessive plural marker -ene, seen in the title of the work Ancrene Wisse "the anchoresses' guide."

Noun Endings

The Definite Article

The normal definite article in AW is the, though very occasionally fragments of the much more complex OE definite article appear:

then, based on the OE masculine accusative singular þone.

Besides representing the definite article, the often functions as the relative pronoun "who" or "which" or as a demonstrative "that." When it is a feminine or plural demonstrative it usually appears as theo.

Though AW's personal pronouns are by and large similar to their modern counterparts, the third person can prove confusing for modern readers.

Personal Pronouns

The main difficulty is that the pronouns for "she" and "they" are usually identical (ha or heo). To decide whether a ha or heo is a "she" or "they," readers must pay attention to the verb endings which in most, but not all, cases provide the pivotal information. For example, ha is must mean "she is" while ha beoth must translate as "they are" (see the verb chart below). Similarly, in the following two phrases, the verbs schal and schulen indicate singular feminine and plural respectively.

Another pitfall for readers is the second person singular objective form the "thee," since it is identical in form to the definite article the as well as the relative pronoun and demonstrative the. As indicated by its modern spelling "thee," the vowel in the second person pronoun the was long, while the relative and demonstrative forms of the had a short and unstressed vowel.

Adjective Endings

Besides endings signaling the comparative (-er, -re) and superlative (-est), the only normal ending possible for adjectives is an -e, and though it is possible to read AW without knowing the nuances of the ending, it will sometimes be useful to know what kind of information it gives. An -e might be added to an adjective for one of the following two reasons:

1) because a definite article (the) precedes the adjective. When this happens, whether the noun is singular or plural the adjective takes an -e ending (see the examples below). In most cases, possessives like "my," "our," "your," "their," "the woman's," etc., act as equivalents to the.

Verbs

Though it is hardly possible to cover the myriad of developments and irregularities in the verb system of AW, it may be useful to mention some of the potential pitfalls. The main complications can be traced back to the OE verb system which had several classes of "weak" verbs (i.e., regular verbs like "walk-walked-walked") as well as seven classes of "strong" verbs (i.e., irregular verbs like "sing-sang-sung").

The following chart gives an overview of endings for the most important categories of verbs, though those familiar with Shakespearean or King James' English ("thou goest," "she goeth") should have few difficulties for the most part. Beyond the regular present and past tense endings, the chart also provides forms for the subjunctive (conditional or theoretical statements: "if I were you," "were she to come," etc.) as well as the imperative (commands: "come!" "look!").

Principal Verb Endings

Many verbs belong to the weak classes Ia and Ib and thus it is impossible to tell the difference between the third person singular (present tense) -eth and the plural (present tense) -eth.

Manuscripts

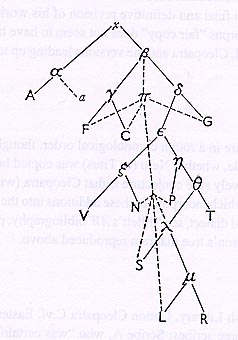

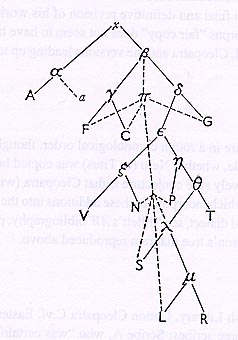

AW is preserved in whole or in fragments in seventeen manuscripts: nine in Middle English, four in French and four in Latin.43 The consensus of scholarly opinion is now that the original language of the text was English and that the French and Latin versions represent later translations.44 Dobson has attempted to work out the manuscript relationships as follows (note that x represents the author's original text while the Greek letters stand for manuscripts which did not survive but whose existence can be inferred. The dotted lines indicate cross-influence, where one manuscript has been collated and corrected with another, however partially).

The manuscript transmission of AW is obviously complex (in fact, Dobson's diagram looks a bit like higher calculus), but the following conjectural account will perhaps give a useful overview, subject to re-evaluation. What complicates the story is that in many cases our only evidence for earlier manuscripts exists in later copies which themselves have been compared and corrected with other versions. With many medieval texts, it is possible to sketch out much simpler tree diagrams (known as stemmas) which describe the genetic relationships of various families of manuscripts. In the case of AW, this process is particularly dodgy, given the intensive cross-fertilization (some would say "contamination") between branches. Dobson was the first to attempt to see through this thicket of relationships, but it should be emphasized that his conclusions have been challenged and that no one has yet undertaken a complete collation (i.e., a word-by-word comparison) of each of the versions. It is possible that our picture of the manuscript transmission (and thus the evolution of the text) may change, perhaps radically, when Millett's full critical edition appears. But for the moment, Dobson's account (with modifications) is the best explanation we have.

The Evolution of the Text

It seems that the author originally wrote his "guide" for three sisters who became anchoresses (perhaps near Wigmore in Worcestershire). This earliest version seems not to have survived, though the Nero MS contains several elements of it. As the community expanded, more copies were produced, perhaps one for each new anchoress and perhaps copied out by the anchoress herself,45 each with incidental changes and additions. Thus, the text evolved. The anchoresses using these texts seem to have been in contact with each other and with the author; they circulated some additions and sometimes collated their versions with others.46 In fact, the messy manuscript evidence is the best testament to a thriving community in which these texts were shared, copied, revised, and compared. At some point, according to Dobson, a scribe, perhaps a cleric or anchoress, prepared a fresh copy (Cleopatra) which a second scribe, perhaps the author, corrected and expanded, often in the margins (see the description of the Cleopatra manuscript below). After working through the text in this way, a scribe produced Corpus (or its immediate ancestor) as a fair or clean copy of what had been worked through in Cleopatra, though Corpus itself has yet more substantial additions and a few deletions. Dobson calls Corpus "a close copy of the author's own final and definitive revision of his work" ("Affiliations," p. 163). After this, curiously, the Corpus "fair copy" does not seem to have been used to produce more authoritative copies. Instead, Cleopatra and the versions leading up to and derived from it continue to be copied.

List of Manuscripts47

The manuscripts listed below are in a rough chronological order, though the exact sequence is difficult to know - for example, whether Nero (or Titus) was copied before or after Corpus is difficult to say. The only relatively sure conjecture is that Cleopatra (with its many marginal additions) came before Corpus (which incorporates these additions into the main text). For more information about provenance and dialect, see Millett's AW bibliography, pp. 49-59. The letters in brackets provide a key to Dobson's tree diagram reproduced above.

English Versions:

Cleopatra [C]. London, British Library, Cotton Cleopatra C.vi. Eastern Worcestershire, c. 1225-30. Dobson identifies three scribes: Scribe A, who "was certainly clerically trained" (Cleopatra, pp. lv-lvi), made the original copy, while Scribe B, responsible for a number of marginal additions and corrections, may have been the AW author himself (Cleopatra, p. cxiv). A much later annotator, Scribe D, modernized the text. Some revisions and additions in the Preface and Part Eight are not carried over to Corpus (Cleopatra, pp. cxix-cxx).

Nero [N]. London, British Library, Cotton Nero A.xiv. Western Worcestershire, c. 1225-50. This version preserves elements of the earliest version of AW (see Explanatory Note to 4.164) and also provides expanded versions of the prayers in Part One (Corpus tends to give only very brief tags). Dobson comments, somewhat crankily: "an innovating manuscript . . . written by a fussy and interfering scribe, constantly archaizing the accidence, attempting to improve the syntax, word-order, and sentence construction (almost invariably with unhappy results), and padding out the phrasing" ("Affiliations," p. 133). Since Morton chose Nero for his influential 1853 edition, it has, in Millett's words, "a special position in AW studies which it retained in some quarters long after its defects had been pointed out" (AW bibliography, p. 52).

Titus [T]. London, British Library, Cotton Titus D.xviii. Southern Cheshire, c. 1225-50. Lacks the preface and a significant portion of Part One. Occasional changes in pronouns suggest that it was adapted for a male audience.

Corpus [A]. Corpus Christi College Cambridge, MS 402, c. 1225-40. Dobson characterizes Corpus as "a close copy of the author's own final and definitive revision of his work" ("Affiliations," p. 163). It incorporates the majority of additions made in Cleopatra (to which it is closely related), along with many more expansions which are preserved in Corpus alone. Millett comments that its "linguistic consistency and generally high textual quality have made it increasingly the preferred base manuscript for editions, translations, and studies of AW" (AW bibliography, p. 49).

Lanhydrock Fragment. Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Eng. th.c.70, c. 1300-50. Consists of a single parchment leaf (employed as a wrapper for another book), containing text which corresponds to 3.238-79. Dobson assigned it to the Nero type in his review of Mack and Zettersten's edition.

Pepys [P]. Cambridge, Magdalene College, Pepys 2498. Essex, last quarter of the fourteenth century. A fairly radical reshaping of AW for a readership of men and women, with a number of revisions, abridgments, and additions, by a compiler with Lollard sympathies. It contains some readings from Corpus or its near relative in Part Four. The text is titled "The Recluse" in the manuscript. See Colledge's article, "The Recluse: A Lollard Interpolated Version of the Ancren Riwle." The manuscript contains several other devotional texts in English and was once owned by the diarist Samuel Pepys.

Vernon [V]. The Vernon Manuscript. Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Eng. Poet.a.1. West Midlands, late fourteenth century. A late, fairly reliable text of AW (closely related to Nero, but with corrections from Corpus or its near relative in Parts Two, Four, and Eight) with some missing folios and omissions. The Vernon Manuscript is a massive, deluxe volume of devotional texts, perhaps assembled for a lay audience.

Caius [G]. Cambridge, Gonville and Caius MS 234/120. Hereford?, c. 1350-1400 A series of excerpts from Parts Three, Four, Five, Six, Seven rearranged in "what seems a completely haphazard order" (Dobson, Origins, p. 296). Judging from spelling, the scribe was not trained in England (Wilson, Gonville and Caius, pp. x-xi). The manuscript also contains extracts from The Lives of the Desert Fathers. See Wilson's edition (p. xiv) for a table matching the Caius extracts to the text of Morton's edition.

Royal [R]. London, British Library, Royal 8 C.i. Fifteenth century. A reshaping of Parts Two and Three of AW. Attributed to the fifteenth-century preacher William Lichfield (see Baugh's edition).

French Versions

Vitellius [F]. London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius F.vii. Early fourteenth century. A translation into French from a manuscript very close to that of Cleopatra, but one which has some additions from Corpus - for this reason, Vitellius is very useful for restoring lost or mistaken readings in Corpus. Vitellius suffered severe damage in the 1731 fire at Ashburnham House, home to Robert Cotton's manuscript collection. The manuscript contains other devotional texts in French.

Trinity [S]. Cambridge, Trinity College, MS 883 (R.14.7). Late thirteenth/early fourteenth century. A translation and adaptation of AW into French, independent of Vitellius. The AW text is "broken up, rearranged, inflated, and embedded in a lengthy 'Compilation,' or series of treatises constituting a sort of handbook or manual of religious living" (Trethewey, p. ix). Two further copies, the second partial, are based on Trinity: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, MS. fonds français 6276 (early fourteenth century); and Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley 90 (late thirteenth/early fourteenth century).

Latin Versions

Latin [L]. Oxford, Merton College MS c.i.5 (Merton 44). C. 1300-50. A translation of AW into Latin; it breaks off after the beginning of Part Eight. Dobson comments that L, "though faithful to the gist of the original, tends to translate more freely than the different idiom of Latin would of itself require; its tendency is to omit and to compress, and in the process it often alters the phrasing at the very points where critical readings might be expected" ("Affiliations," p. 134). Though it related in some way to Titus, it also has corrected readings from Corpus or its near relative in Parts Four and Eight ("Affiliations," pp. 135-36). There are three other Latin versions based on or related to the Merton College MS: Oxford, Magdalen College MS Latin 67 (c. 1400), with Part Eight altogether missing; London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius E.vii (early fourteenth century), which survives only in charred fragments; and London, British Library, Royal 7 C.x (beginning of sixteenth century), which has a significant omission, ending after the first 9 lines of Part Eight, as does Merton.

Related Texts

Two other groups of texts - the so-called Katherine and Wooing groups - are closely related to AW in language, date, and subject matter. It is likely that they were intended for the same audience of anchoresses, and that they came from the same author or school, though as Millett rightly cautions, "The linking of AW, KG, and WG as a larger group is . . . modern, and there is still no general agreement on whether we are dealing with a single, well-defined oeuvre or with a scattering of works by different authors and with ill-defined boundaries. Nevertheless, there are good reasons for treating these works at least provisionally as a single group with a common origin" (AW bibliography, p. 6), especially since they appear together in various combinations in thirteenth-century manuscripts.

The Katherine Group, preserved most fully in MS Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley 34, consists of five texts in prose: the lives of three virgin martyrs: 1) St. Katherine (in which Katherine defends herself against a group of pagan scholars), 2) St. Margaret (who does battle with the devil in the form of a dragon, specifically with the weapon of prayer), and 3) St. Juliana (who captures a demon and makes him explain the techniques he uses to tempt the faithful), along with two prose treatises: 4) "Hali Meiðhad" ("Holy Maidenhood," a vivid and often radical discussion of the value of virginity in comparison to that of marriage and widowhood - it paints an unpleasant picture of married life from a woman's point of view) and 5) "Sawles Warde" ("The Keeping of the Soul," an allegorical treatise in which the soul is represented as a house belonging to a husband called Wit and a housewife called Will: to prevent an impending robbery a variety of allegorical figures such as Caution, Fear, Justice, etc., advise the couple). AW refers explicitly to "ower Englische boc of Seinte Margarete" (4.796), and various texts in the Katherine Group may well have been intended as devotional reading for the anchoresses,48 who in Part One are urged to keep themselves occupied with reading in English or French (1.340) and who in Part Four are advised to read as a remedy for sloth, a remedy perhaps more potent than prayer itself:

The following chart, adapted from Shepherd's introduction (p. xiv), shows the manuscripts in which some combination of these texts occur.

Later Influence of AW

AW exerted a strong influence on the devotional literature which followed it, particularly that of the fifteenth century. The following texts contain excerpts or adaptations from AW: The Tretyse of Loue (printed in 1493), the Regula Reclusorum Dubliniensis ("The Rule of the Recluses of Dublin," early fourteenth century), The Chastising of God's Children (early fifteenth century), The Poor Caitif (latter half of fourteenth century), the Gratia Dei (an English version of de Guilleville's Péligrinage), William of Lichfield's Treatise of the Five Senses (fifteenth century), the Vernon Manuscript's The Life of Adam and Eve (late fourteenth century),49 as well as The Pater Noster of Richard Ermyte and a prose treatise on the Seven Deadly Sins (see Diekstra's "Some Fifteenth-Century Borrowings from the Ancrene Wisse").

Sources and Background

Though scholars have identified no single direct source for AW, they have identified a myriad of borrowings and influences from a vast range of texts including biblical commentaries, other religious rules, patristic writings (particularly those of Jerome, Gregory, Augustine, and Bernard), theological and preaching manuals, and various Latin treatises.50

Moralities on the Gospels

One proposed source deserves special attention and perhaps special scrutiny. The so-called Moralities on the Gospels, as Anne Hudson first discovered, shares a number of interpretations, images, and patristic quotations with AW (Dobson, Moralities, p. 1). In his study and partial edition, Moralities on the Gospels: A New Source of Ancrene Wisse, Dobson finds over one hundred parallels between the two texts, some rather loose, and concludes that Moralities is "a major source" of AW, "perhaps the most important single source yet discovered" (p. 21). Some of the most striking similarities include Moralities' comparison of the hypocrite to a flightless ostrich (AW Part Three), the sixteen attributes of confession (AW Part Five), the four loves (AW Part Seven), the idea of Christ's body as a shield (AW Part Seven), as well as a number of images: Greek fire, speech as mere wind, the cross-like shape of birds, the hidden hand of Moses, confession as the cleaning of a room, etc. Many of the reviewers of Moralities, however, have expressed scepticism about Dobson's conclusions. Joseph Wittig, for example, thinks that many of the parallels Dobson saw in Moralities "are on the whole unpersuasive," since they also occur in other sources known to the AW author (p. 189). But the sheer number of parallels, however loose, is interesting, and the two texts may derive from a shared tradition of preaching and exegesis, or may draw on another, as yet undiscovered text.51

Other Religious Rules

The AW author clearly knew the anchoritic rule which Aelred of Rievaulx wrote for his sister between 1160 and 1162, De Institutione Inclusarum "Concerning the Instruction of Recluses" (lit., enclosed women), from which he seems to have borrowed the key concept of the inner and outer rules. Other borrowings from Aelred are clustered mainly in the Preface, Parts Two, Six, and Eight, and many of them concern the regulation of external behavior. See the Explanatory Notes for specific parallels. A strong case can be made that AW draws on some combination of the Augustinian Rule, the Augustinian Institutes of Prémontré, or the Domincan constitutions (see the section on "Authorship" above), and it is possible that the AW author knew other anchoritic rules, such as the tenth- or eleventh-century rule of Grimlac of Metz, the Liber Confortatorius by Goscelin (c. 1080), certain letters of Anselm (c. 1103-07) directed to anchoresses,52 or the Carthusian Consuitudines of Guigo (Barratt, "Anchoritic Aspects," pp. 37 ff.).

The Bible and Bible Commentaries

As Shepherd writes in the excellent introduction to his partial edition of AW,

Reference Works

AW may make use of a variety of biblical reference works which were coming into being at the time of its writing. Shepherd mentions the alphabetic handbooks known as Distinctiones (p. xxxviii), which listed alternative meanings for biblical words and concepts along with allegorical interpretations and etymologies,53 and, in fact, Moralities on the Gospels is probably best viewed as a set of Distinctiones. The thirteenth-century passion for preaching gave rise to other kinds of reference works, particularly collections of exempla (sermon stories) as well as books called Similitudines (listing a variety of similes and metaphors to explain moral and biblical concepts). For example, the following comparison from an entry titled intention in the Similitudinarium of William de Montibus (1140-1213) explains with a colorful comparison how intentions can go wrong: "If you carry flour in the wind, the wind may scatter it."54 Similitudines helped preachers to find instructive, startling, or entertaining comparisons for their sermons, and they often seem to be derived from the life-world of the laity. AW is fond of such startling comparisons - God's love as Greek fire (7.223 ff.), the spiritual life compared to rowing upstream (2.714 ff.), flatterers and backbiters as the devil's toilet attendants (2.433 ff.), Christ as a village wrestler (4.1240-51) - and it may be that the stimulus for some of them came from Similitudines. Unfortunately, the vast majority of surviving Similitudines have never been edited or translated.

The Lives of the Desert Fathers

AW cites several anecdotes from this collection, which it calls the Vitas Patrum. Written first in Greek and translated into Latin, The Lives of the Desert Fathers consists of several originally separate works, all offering accounts of the lives and sayings of the desert saints (both men and women).55 Though these stories have a particular relevance to anchoresses (see the section on Desert Spirituality above), it is important to realize that The Lives of the Desert Fathers was the forerunner of the exempla collections which multiplied in the thirteenth century, and its stories of heroism in the desert often made their way into popular preaching (see Welter's L'Exemplum dans la littérature religieuse et didactique du moyen age, pp. 28-42).

Patristic Sources

Among the most cited Latin authors in AW are Jerome, Augustine, and Gregory the Great, along with the later writers Anselm and Bernard. It is difficult to know whether the AW author knew these writers in full texts or whether he found the relevant quotations in collections or other handbooks. See the Explanatory Notes for remarks on specific sources.

Anglo-Latin Sources

At the moment, we know very little about how AW may have drawn on prominent twelfth- and thirteenth-century Anglo-Latin authors like Alexander Neckam (1157-1217), Archbishop of Canterbury Stephen Langton (died 1228), William de Montibus (1140-1213), and others. Some tentative attributions have been made (see the scattered references in Millett's AW bibliography), but Anglo-Latin writings from this age are a vast terra incognita: the majority have never been edited.56

Critical Reception

The Beginnings

Three projects have dominated nineteenth- and twentieth-century scholarship on AW. The first, the search for the identity of the anchoresses and the AW author, has already been discussed in the sections on Authorship and Audience, above. The second is easy to take for granted - that is, the search for the texts of AW, the subsequent editing of them, and the working out of the relationships between them. The third, the search for sources, continues (see the section on Sources above), along with some efforts at cultural assessment of the work.

EETS Project

The original aims of the Early English Text Society's plan to publish all the versions of AW are shrouded in some mystery, though it seems clear that they were intended in some way to provide the raw material from which a critical edition could be constructed. The first of the editions, that of the Latin versions, "was begun," as D'Evelyn explains, "some time ago as part of a joint undertaking to publish all surviving manuscripts of [Ancrene Riwle]. Once the extant texts are available the problems with which the Ancrene Riwle has been hedged about can be referred back at least to a common body of information and a common system of reference" (p. viii). The first phase of this monumental project is nearing completion: with Bernard Diensberg's edition of the Vernon manuscript of AW (forthcoming in 2000) all known manuscripts of AW will be represented.

The only criticism which one might voice about the EETS editions concerns their somewhat Spartan appointments - that is, they provide no glossaries, notes, or general introductions, and focus much energy on providing diplomatic texts of their manuscripts (i.e., they are essentially facsimiles in print), with no emendations or word division. As useful as they are, the EETS editions are almost impossible to use as reading texts. It is hoped that the current edition will provide a more accessible student's edition of the entire Corpus version. In turn, Bella Millett's forthcoming full critical edition will work out much more completely AW's sources and manuscript relations and should bring to a close the nearly century-long search for a full scholarly text of AW.

Style

Many studies of AW in roughly the middle part of the twentieth century concentrate on issues of vocabulary and style. This focus was appropriate for the way AW once fit into literary history - as a representative of English style in a time when the language was threatened by the dominance of French and Latin (see the section on Ancrene Wisse's Place in Literary History above).

One important question revolved around the exact percentages of French, Norse, and native elements in the AW vocabulary. Cecily Clark showed that AW has a relatively high percentage of French loans (about 10% for Parts Six and Seven alone) compared to the percentage (2-6%) in the Katherine Group texts ("Lexical Divergence," p. 120). And in a remarkable series of detailed studies Arne Zettersten turned his attention to each of the components of AW's vocabulary (French, Norse, and native), working out a number of etymologies and definitions (see Middle English Word Studies, Studies in the Dialect, and "French Loan-words"). Somewhat later, Diensberg compared the language of the fourteenth-century Vernon manuscript to that of the much earlier Corpus and Nero versions, concluding that Vernon modernized the language of AW in part by introducing more Romance loanwords (a total of 6-7%) compared with the overall proportion for Corpus (approximately 3% for the entire text ["Lexical Change," pp. 309-10]).

On general issues of style, Rygiel ("A Holistic Approach") proposed a formalistic approach to the AW's style based on a modified kind of close reading, while two studies by Clark ("Wið Scharpe Sneateres") and Rygiel ("'Colloquial' Style") warned about the dangers of assuming an uncomplicated colloquial element in AW's style.

The imagery of AW also captured the attention of many scholars. Perhaps the most important study is Janet Grayson's Structure and Imagery in "Ancrene Wisse," which shows how images in AW tend to build into complex, cumulative patterns. See for example her analysis of various images of enclosure including the anchorhold, grave, body, womb, nest, etc. (chapters 2 and 3). Jocelyn Price also focuses on images and analogies, stressing the radical nature of metaphor and simile in AW (see Explanatory Note to 6.376).

Women's Spirituality

In the 1980s, AW began to find a new place in the literary history of early Middle English literature. More and more, scholars began to turn to AW as a witness of the lives and spirituality of medieval women. The turning point was Linda Georgianna's important book The Solitary Self: Individuality in the Ancrene Wisse. In this study, Georgianna finds in AW a concern for a conscious and reflective inner life and places it in the context of the twelfth-century Renaissance:

As the eighties and nineties progressed, feminist scholars began to broaden this picture by scrutinizing the construction of gender in AW, a central issue. Among the most important contributions on this topic is Elizabeth Robertson's study, Early English Devotional Prose and the Female Audience, which places the male author's conceptions of gender and sexuality in the foreground:

Following the lead of Carolyn Walker Bynum in her two influential studies Jesus as Mother and Holy Feast, Holy Fast, a number of scholars emphasize that female spirituality as conceived in AW is linked not to the spirit but lived through the body. Jocelyn Wogan-Browne, for example, writes that much of AW's "account of sense experience focuses on entry and impermeability, enclosure and leakage, sealing and opening . . . . The recluse's bodily experience in the cell is represented as a constant struggle for regulation of these permeabilities."57 Karma Lochrie ("The Language of Transgression") and Robertson ("Medieval Medical Views") add to the discussion by looking at affective and medical assumptions about the female body.

One of the most important feminist projects has been the recovery of women's voices which in the Middle Ages were often lost, ignored, or suppressed. Robertson provides insight into this issue in "The Rule of the Body," where she stresses the fact that women's voices as they appear in AW are constructed by the author and tend to represent the female voice as querulous and wrong-headed. AW holds up silence and passivity as the highest ideals for women (p. 130). Anne Clark Bartlett's Male Authors, Female Readers makes a similar argument about Aelred's anchoritic rule, suggesting that Aelred makes an explicit link between female speech and sexual activity (p. 45).

The Question of Mysticism

Whether or to what extent the spirituality of AW is mystical remains a topic of debate. Sitwell, in his introduction to Salu's translation, was perhaps the first to suggest that the interests of the AW author centered more on moral or pastoral theology rather than the contemplative life (leading to mystical union with God) prized by Rolle, Hilton, and other fourteenth-century mystics (Salu, pp. xvi-xxi). Shepherd endorsed this idea, writing that "[t]here is little point in speaking of AW as a mystical work" since the author "does not exalt the life of pure contemplation. It is a life of penitence he urges throughout" (pp. lvii, lviii). This view, as Watson points out, may be somewhat extreme, however. Though Watson suggests that AW does not see the spiritual life as a progressive path towards direct union with God in the way that later mystics did, nevertheless the intensity of emotions surrounding the inner life in AW for him approaches that of the English mystics of the next century ("Methods and Objectives," pp. 143 ff.).

Perhaps the most mystical passage in the entire AW appears in a seemingly unlikely place, in Part One's discussion of the anchoresses' prayers and liturgy (as part of the outer rule). Here, after the kiss of peace in the mass, the anchoress is to enter into a mystical union with God via the Eucharist: "After the kiss of peace, when the priest sanctifies [the Host] - forget there all the world, be there completely out of your body, embrace there in sparkling love your lover, who has descended into your bower from heaven, and hold him firmly until he has granted you all that you ever ask" (1.203-06). In the vast bulk of AW, on the other hand, the anchoress remains firmly rooted in a (gendered) body of pain, and the promise of spiritual embraces must, by and large, wait for the next life. It is curious that even Part Seven, which turns to spiritual love, defers the embrace of bride and bridegroom, knight and lady. Christ, in the guise of a romantic knight, makes the offer of love, but for most of Part Seven, the feminized soul refuses his embrace. AW also differs from the writings of later English mystics like Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe, especially in regard to devotional practices. While their books are built around the direct experience of mystical visions, the AW author encourages his charges to reject such sights as possibly infernal temptations: "Consider no sight that you see, either in sleep or while awake, anything but error, for it is nothing but his (i.e., the devil's) guile" (4.561-62). A bit later, "dreams" and "showings" are equated with the devil's witchcraft: "his deceitful witchcrafts and all his tricks, such as lying dreams and false visions" (4.1103-04). In this sense, AW may betray a male fear of women's spirituality.

In her book Margery Kempe describes meditations which seem to be in the mainstream of late medieval affective piety: she imagines biblical scenes in great detail, sometimes projecting herself in them, much as the Pseudo-Bonaventuran Meditations on the Life of Christ encouraged believers to do. Aelred includes a similar set of meditations at the end of his De Institutione Inclusarum ("Concerning the Instruction of Recluses"), where he encourages his sister and other anchoresses to imagine scenes from the past (Old and New Testament scenes), present (personal sins and gifts), and future (death, Last Judgment, heaven, and hell). In one early meditation, for example, the anchoress is to imagine herself in Bethlehem at the manger: "with all your devotion accompany the Mother as she makes her way to Bethlehem. Take shelter in the inn with her, be present and help her as she gives birth, and when the infant is laid in the manger break out into words of exultant joy. . . . Embrace that sweet crib, let love overcome your reluctance, affection drive out fear."58 By and large, AW encourages its readers to approach the spiritual life not through such meditative exercises, but through a relentlessly allegorical and exegetical way of reading. Even the meditations on the passion embedded in Part Two, though they have their affective side, are mainly tied into arguments about the body and how it is to be regulated.

Editorial Principles

This edition aims to provide a reading text of the Corpus version of AW, though it is not a full critical edition in one important sense: it is not based on a full collation (i.e., a painstaking comparison) of all the versions. Instead, other manuscripts are consulted only when Corpus has gone wrong in some way, either by recording a mistaken form or by omitting text inadvertently.

Though this method may seem close to "best text" editing, it is somewhat different in spirit. In "best text" editing, an editor decides which of the many versions is closest to the author's intended text and then reproduces it with a minimum of editorial intervention.59 (Eclectic editions, by contrast, might take readings from any of the versions, provided these readings can be deemed authorial - though in practice such judgments are often very subjective.) The main difference between the editorial approach employed here and best text editing has to do with the attitude towards authorial intention. The Corpus version was not chosen as the basis of this edition because it represents, in Dobson's words, "a close copy of the author's own final and definitive revision of his work" ("Affiliations," p. 163). The Corpus version is simply one of the most interesting versions, since it incorporates a number of earlier additions as well as its own expansions. After surveying twentieth-century editorial theory, Millett suggests that AW changes and shifts so much that even such a revision as Corpus cannot be viewed as definitive or final ("Mouvance," p. 18). It seems best to view AW as an evolving text - each of the versions is worthy of study (and thanks to the far-sighted EETS project to edit all the versions separately, such study is possible).

One problem with placing too much emphasis on authorial intention is that such an attitude tends to make idiots of scribes, who in this textual model can do nothing but either preserve or (more likely) corrupt the author's original text, rendering "unauthoritative" versions unworthy of interest (see Dobson's description of the Nero manuscript above). Though scribes clearly make mistakes, it seems to me possible to view the production of AW texts as in some sense collaborative, involving not just the author's intentions but also the suggestions and additions of its female audience and its scribes. In this respect it may be a more useful cultural document than the original.

Textual Notes

Some effort has been given to make the textual notes accessible to ordinary readers and to avoid the nearly indecipherable calculus of variants found in some critical editions. Each variant is recorded separately and the reasoning behind each emendation is given. Any italics or brackets in the main text of AW indicate that Corpus has been changed in some way and that interested readers can find a textual note on the subject.

Regularization of Spelling

In accordance with the goal of this series I have regularized the spelling of the text: Þ/þ and ð have been transliterated as th, while yogh (3) almost always appears as y. In addition I have brought variations between u/v and i/j into line with modern practice. Since the goal of this edition is to provide a convenient reading text for students, I have hyphenated difficult compounds.

Same Page Glosses

The aim of the same-page glosses is not to give a fluid, running translation of the text (for this consult the excellent translations of White or Savage and Watson), but rather to provide the literal sense of the Middle English text as an aid for understanding it on its own terms. Sometimes the glosses themselves will be somewhat challenging to modern idiomatic sense, though they do provide guiding suggestions and supply words not in the Middle English (in parentheses) to complete the meaning. Since biblical quotations in AW are often loose, either because they are cited from memory or consciously simplified, they are translated freshly rather than taking them from modern English translation of the Vulgate.

This edition provides a reading text of the entire Corpus version.

Ancrene Wisse's Place in Literary History

It may at first seem startling that such a vivid and sophisticated vernacular prose as one finds in Ancrene Wisse (henceforth AW) and its related texts sprang to life in the Welsh borders and at a time (the early thirteenth century) when English was not at all a prized medium for serious religious instruction. AW, however, was written in a vernacular literary culture which in some senses stretched back to the late Anglo-Saxon period. The homilies of Ælfric and Wulfstan continued to be copied well into the twelfth century in Worcester, where they were also annotated and studied in the thirteenth. As Thorlac Turville-Petre writes, "This suggests a tradition of respect for works in English that must have itself acted as a stimulus to writings throughout the thirteenth century. Indeed, the quality and diversity of the English texts composed or copied in this region is striking."3 These texts include such important monuments of early Middle English as Layamon's Brut and The Owl and the Nightingale as well as MS Digby 86, which contains Dame Sirith, perhaps the earliest fabliau in English. The situation must have been different in the East Midlands, which gave birth to the much rougher Ormulum.

Thus, in West Midlands English, the AW author found a language already adapted to literary uses. R. W. Chambers, in his classic study, On the Continuity of English Prose from Alfred to More and his School, argued that the AW author carried on the work of late Old English writers such as Æthelwold and Ælfric, and that AW acted something like a linguistic Noah's arc, preserving English traditions in a time of Anglo-Norman and French deluge: "The Ancren Riwle therefore occupies a vital position in the history of English prose. Its popularity extends over the darkest period of our literature."4 As Bella Millett has pointed out, however, this view of AW and its related texts as vessels of "Englishness" ignores the strong continental influence on the AW's exegetical prose which was shaped in large part by twelfth-century Latin literature.5 Though it has some important connections to late Old English, then, AW's vernacular prose does not descend directly from it.

Why the Vernacular?

One question remains, however: Despite the fact that the AW author had a form of literary English at his disposal, it is not at first clear why he chose it as a vehicle for the rather advanced religious instruction of AW when, in the early thirteenth century, Latin or French would have been a more natural medium.6 One answer to this question lies in the nature of AW's audience, a group of quasi-lay women, some of high birth. Though they could apparently read French (see 1.340), the fact that almost all the Latin quotations are translated into English suggests that their literacy in Latin was limited and thus that they were not nuns. AW was composed in English, then, because it was written for lay people, though of a very special type (see the section on "Audience" below), because it was written for women (whose educational opportunities were much more restricted than those of men), and because it was composed in a region which valued English literary culture.

The Anchoritic Life

Medieval anchorites, as strange as it may seem to us, sought to withdraw so radically from the world that they had themselves sealed into cells for life. In fact, the word anchorite comes ultimately from the Greek verb anacwre-ein, which means "to withdraw." Anchorites (both men and women) withdrew from the world not only to avoid physical temptation, but to engage in the kind of spiritual warfare practiced by desert saints like St. Anthony (the founder of Western monasticism), who around 285 A.D. wandered into the Egyptian desert searching for God through complete solitude and who attempted to tame the wickedness of the body with physical suffering and discipline.

Desert Spirituality

In the fourth and fifth centuries, a number of holy men and women like St. Anthony retired to the Egyptian desert to seek a severe life of solitude. In many senses they were something like spiritual athletes. In fact, the word ascesis (from which asceticism derives) referred originally to the regimen of exercise practiced by athletes. AW refers admiringly to some of the superstars of the desert: Anthony, Paul the Hermit, Macarius, Arsenius, Sarah, Synceltica, Hilarion, retelling their feats of perseverance and discipline from a text known as the Vitas Patrum (The Lives of the [Desert] Fathers).7 Peter Brown manages to recapture some of the excitement of desert spirituality, and his remarks are worth quoting at some length: